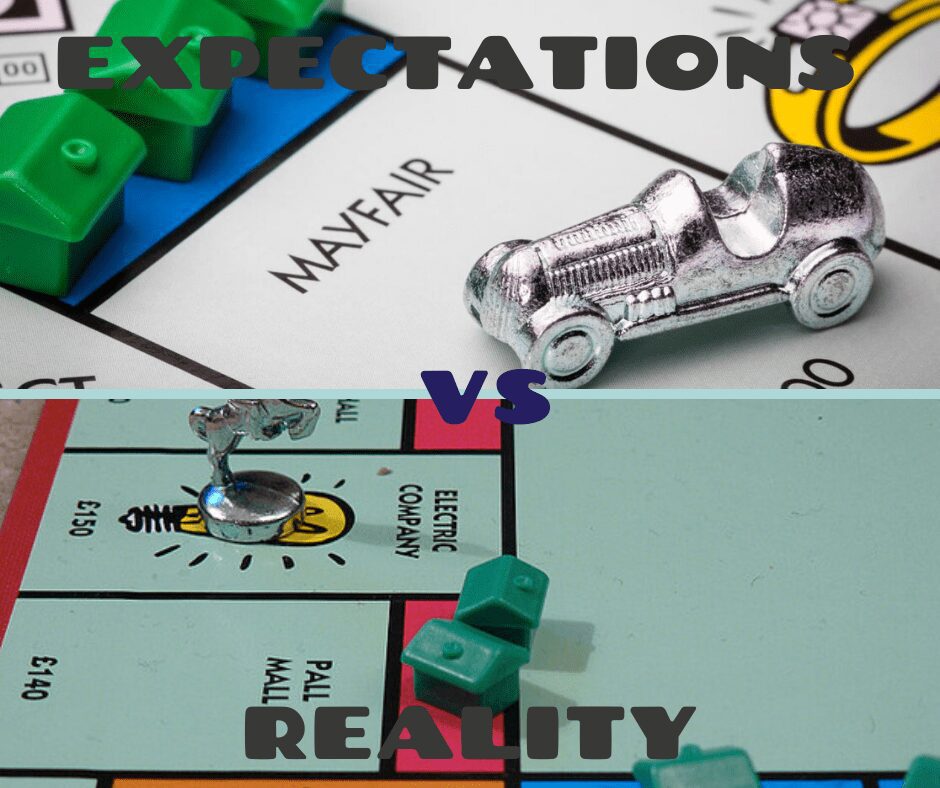

Technology startups are always a roll of the dice. Like a game of Monopoly played with real money, the normal rhythm is always two steps forward for every one step back.

But the outbreak in March of novel coronavirus COVID-19, a pandemic that brings the entire global economy to its knees, is like being on Mayfair* with only $156 and a get-out-of-jail-free card. You have an entire board filled with hotels, waiting for you to land and charge rent, but there’s $200 for passing go and a big stack of money on free parking waiting for you, if only you roll right.

Except that Sydney is not Mayfair. It’s more like being on Pall Mall**; not a bad place, a little off the beaten track, but only a quarter around the board. Indeed, within the Australian startup network, it has long been accepted that Australia is actually one of the worst places to start a technology-driven business. although Sydney is ranked the 23rd best city in the world for its start-up ecosystem, if you dig a little deeper into the figures, you find that the traditional Australian attributes of good climate and easy lifestyle pull Sydney up the ranking, outweighing more business-focused criteria like access to capital or network connectivity. But offset this against the incredibly high cost of living in Sydney and it augers poorly for a start-up company during a period of unprecedented economic shock.

Where to live as an entrepreneur during Covid

Cities in the United States dominate the list of best places to start a technology company. Ten of the top 20 start-up ecosystems, in fact, are in the United States. Only London and Berlin feature in the otherwise all-US list that has Silicon Valley, and New York City as the stop cities globally to start an innovative high technology company.

Start-ups are small businesses. But small businesses without revenue. The whole gamble of start-ups is around the genius of idea. That someone has invented something that no-one else has thought of, and managed to make a product out of it and commercialised it, is the currency of start-up world. The potential market size of said product is what attracts investors and the commercialisation of that product is what convinces them to part with their money and place a bet on a long shot.

Early data on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic was confronting. Chinese venture capital firms contracted by 57 percent since the beginning of the year. Investors are running scared, with losses from the stock market (the supposed safe investment) reducing the available pool for start-ups (the risky ventures).

But the real impact is not just in investment funds now, it is around a recession or a depression. During the 2000 and 2007 recessions, venture capital deals were around US$86 billion lower than in 2019. Investments took around three years to recover from each of those shocks.

For start-ups, the problem is, as ever, cashflow. As Arnobio Morelix of Startup Genome points out: 41% of startups globally are threatened in what we call the dead zone.

41% of startups globally are threatened in what we call red zone; they have three months or less of cash runway left. Many very young startups live with only a few months in cash, were in that situation already before the crisis but the crisis put 40% more of them in that precarious position.

Commercialisation of invention is, thus, the key indicator on the health of a start-up ecosystem. Again, the US leads the world. Only Israel comes close.

Australia is a very poor place to bring a new product to market. Australia fails in four key areas: Commercial viability, weak collaboration opportunity, structural barriers placed by government and cultural barriers around the concept of startups.

If we look to the United States, many of the barriers start-ups in Australia face do not exist. For example, access to the top talent: Although Australia is ranked as seventh most attractive place to work among highly-educated global professionals, its attractiveness is principally driven by lifestyle rather than professional challenge.

This is in contrast to Silicon Valley, New York or even Denver, where the brightest and best of the world congregate to bring new ideas to life. Elsewhere, cities attract talent, which grows the city’s economy through new ideas. Australia (together with New Zealand) tends to attract people looking for warmth, safety and security, rather than pioneers in their field.

A silver lining in the Covid cloud

Yet Coronavirus could prove to be the apple that grows from this seed. Australia appears to have escaped the worst of the COVID-19 initial pandemic. Time will tell, of course, but the United States is likely end up being the most heavily impacted nation on earth (unless Brazil or Russia overtake). Freedom of movement, like other freedoms, is highly cherished in the US. In fact, it’s probably unconstitutional to block free movement between the states.

By contrast, Australian states erected concrete walls between themselves. This has been followed by state governments payouts to support small business owners in order to retain not only business but innovation within their state borders. Here, state governments are looking at amending their byzantine procurement rules that have long shut start-ups out of lucrative contracts. This would help, although many start-ups will have disappeared into a cashflow hole by the time the legislation makes its way through the now shuttered state parliaments.

Challenges faced by entrepreneurs during Covid-19

When it comes to start-ups, Australia is less brutal than in the United States. Again, because people come to Australia because it’s safe and warm, the cut-throat do-or-die approach of Silicon Valley doesn’t translate here. Whereas within two weeks from the first shelter-in-place order in California on March 19, a quarter of Silicon Valley pre-Series A companies had already made layoffs, in Australia, most start-ups were hanging out for the government-funded JobKeeper grant.

Venture capitalists always advise their startups to respond quickly to a crisis with cost cuts, in order to focus the rest of the team on the latest pivot. Slashing rent, marketing and staff are the three areas to reduce if you want to lengthen your runway, as the industry jargon goes. As a founder of an Australian startup, Vloggi, who has followed all three of these suggestions, and cut our burn by 35%, I can tell you I’m in the minority. Over there, the mentality is self-help, here it’s government-help.

As a point of reference, Voyager HQ, the New York incubator of which are virtual members, is circulating a list of start-up resources compiled by JetBlue Technology Ventures. Even back in early April, the list had 13 pages of two-line entries for bank, governmental and private initiatives aimed at the US start-up sector. The Australian equivalent, curated by Innovation Bay, runs to a mere five pages, with each entry seven or eight lines deep.

But at times like these, it’s no longer a competition, more a fight for survival. Central to the US relief is the small business administration’s disaster assistance packages under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) act. Yet, these are loans, rather than cash hand-outs (albeit on easy terms). Here in Australia, it’s the JobKeeper allowance that will help start-ups who pay developers.

As ever, Australia is caught midway between Europe and the United States. France has gone furthest in explicitly funding the start-up sector. Current French president Emmanuel Macron has vowed to overtake Britain, weakened by Brexit, as Europe’s primary start-up landing pad for US start-ups through tax cuts and bureaucracy reductions. As part of this, the French government singled out start-ups as in need of COVID assistance, throwing a €4 billion (US$4.33 billion) liquidity support package at early stage digital companies under digital minister Cédric O.

Australia, meanwhile is encouraging low-interest loans from banks, while also underwriting salaries. There has been talk for weeks of either state or federal governments specifically aiding start-ups, but at time or writing, none was forthcoming.

The principal challenge start-ups face globally is access to capital. Investors have gone to ground, preferring to count their losses on the stock market than jump into anything riskier. The exception is, of course, Silicon Valley, where early stage fund SeedInvest is actively scouting for ground-breaking companies that can bounce out of the current crisis and make its fund members multiples of their investment. They are looking for start-ups in medical tech, protective wearables, and video collaboration, the three hottest stocks right now. US cities have the brightest minds working to crack these global problems

But Australia is different. Melbourne and Sydney often vie with Swiss cities as the world’s most liveable and Australian cities are among the world’s safest, yet benchmarked against rivals, Australia’s largest cities perform relatively poorly for attracting global talent. Australia can invent great things, but struggles to bring them to market. The Cochlear implant was patented in Australia and commercialised globally. In contrast, almost every other Australian invention was either patented elsewhere or commercialised overseas, mostly in the United States. The rotary clothes dryer, for example, was patented in Pennsylvania some 14 years before its ‘invention’ as the Hills Hoist.

Perhaps the most telling reaction to the current crisis was the incubator space. In the United States, Y Combinator – the launch pad for Airbnb, Dropbox and 100 other unicorn start-ups valued at more than US$150 million each- announced it would fast-track a handful of promising startups through its application process and fund them immediately. In Australia, meanwhile, most incubators quietly shut their doors, postponed programs and refunded monies back to their fund investors.

Admittedly, Y Combinator singled out those start-ups working on tests or diagnostics, treatments and vaccines, hospital equipment, and monitoring infrastructure, so its bets were firmly hedged in the short term.

As with other sectors, unknown is the core feeling among start-ups. No-one knows where the world is heading, the demand is heading or where the policy is heading. Right now it’s survival and then regroup and play to take over the future once again. Roll those dice again!

This article is an editorial version of a forthcoming research brief being prepared for the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

______________________________

*Mayfair = Boardwalk in the standard US edition, Rue de la Paix (or Avenue Foch in more recent editions) in Paris edition,

**Pall Mall = St. Charles Place in the US edition, or Boulevard de la Villette in Paris